Moscow, the cultural heart of Russia, has nurtured generations of extraordinary actors whose talent has shaped both Russian and global cinema and theatre. This list highlights ten iconic performers — born in the capital — whose artistry, depth, and charisma have left an indelible mark on the performing arts. For each, we explore their key contributions, signature roles, and a glimpse into their personal worlds.

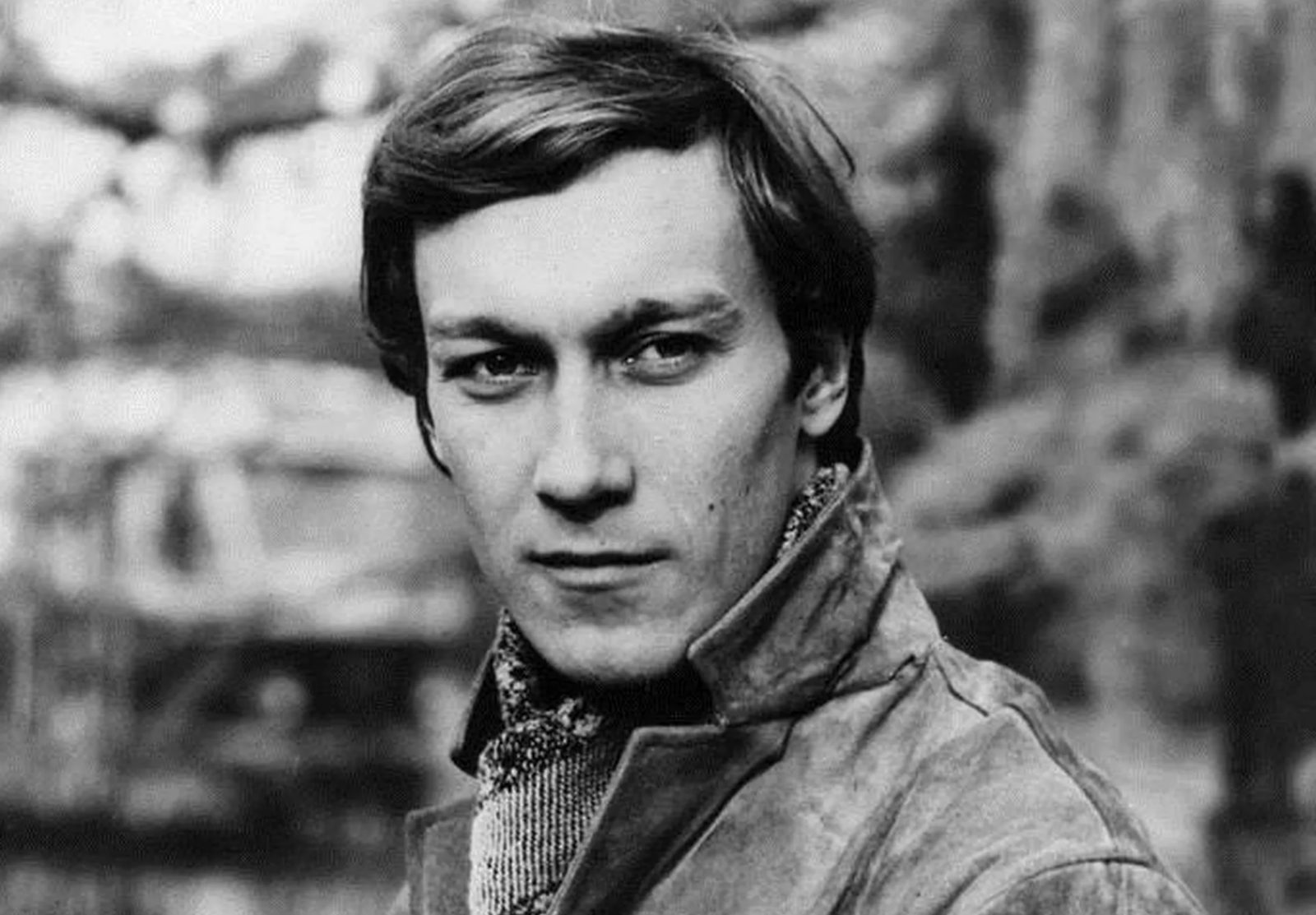

Oleg Yankovsky (1944–2009)

Artistic Legacy

Oleg Yankovsky was a master of subtlety and intellectual presence, whose performances blended psychological depth with philosophical inquiry. At the Lenkom Theatre, he became a cornerstone of productions like Hamlet and Till Eulenspiegel, where his ability to convey inner conflict through minimal gestures set him apart. His screen roles — from the enigmatic traveller in Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror (1975) to the witty Konstantin Riazanovsky in The Pokrovsky Gate (1982) — revealed a rare capacity to inhabit both avant‑garde and popular genres.

Signature Roles

Yankovsky’s portrayal of Hamlet (1976) is often cited as one of the most profound in Russian theatre history, merging Shakespearean tragedy with a distinctly Soviet existentialism. In The Pokrovsky Gate, his comic timing and warmth made the character an emblem of Moscow’s intellectual milieu. Later, his role in We Are from Jazz (1983) showcased his musicality and charm, proving his versatility across genres.

Personal Anecdote

Despite being born in Kazakhstan, Yankovsky considered Moscow his true home. He once joked that his nomadic childhood (his family moved frequently due to his father’s military service) prepared him for the transient life of an actor. Colleagues recalled his quiet discipline: he would arrive at the theatre hours early to meditate and prepare, believing that “the actor’s body is an instrument that must be tuned daily.”

Innokenty Smoktunovsky (1925–1994)

Artistic Legacy

Smoktunovsky redefined Russian Shakespearean performance with his 1954 Hamlet at the Maly Theatre, a role that fused existential anguish with spiritual longing. His collaboration with director Grigori Kozintsev on Hamlet (1964) brought him international acclaim, while his stage work at the Moscow Art Theatre (MKhAT) — including Ivanov and Three Sisters — demonstrated his mastery of Chekhovian nuance.

Signature Roles

His Prince Myshkin in The Idiot (1958), based on Dostoevsky’s novel, remains a benchmark for portraying moral purity amid chaos. In Dead Souls (1984), his depiction of Pavel Chichikov revealed a sly, almost tragicomic dimension to the character. Critics praised his ability to make literary giants feel human and immediate.

Personal Anecdote

Smoktunovsky’s path to stardom was unconventional: he fought in World War II, was captured, and escaped multiple times before pursuing acting. He later said, “War taught me that every moment is precious — that’s why I never wasted a second on stage.” His humility was legendary; he often declined awards, insisting that “the role itself is the reward.”

Andrey Mironov (1941–1987)

Artistic Legacy

Mironov was a rare blend of comic genius and dramatic depth, equally at home in satire and tragedy. At the Moscow Theatre of Satire, he starred in classics like The Government Inspector and The Marriage of Figaro, where his physical comedy and vocal precision delighted audiences. His film roles — particularly in The Diamond Arm (1969) and Twelve Chairs (1976) — cemented his status as a national treasure.

Signature Roles

In The Diamond Arm, his portrayal of the bumbling smuggler Gena Kozodoyev became iconic for its slapstick brilliance and heart. As Ostap Bender in Twelve Chairs, he brought a poetic edge to the con man’s schemes. Off‑screen, he was a gifted singer; his renditions of songs like “Ostap’s Waltz” added layers to his characters.

Personal Anecdote

Mironov was known for his perfectionism: he rehearsed dance numbers for The Marriage of Figaro until his feet bled. Friends recalled his generosity — he often gave away his earnings to colleagues in need. Tragically, he collapsed on stage during a performance of The Government Inspector in 1987, dying days later. His final words to his co‑stars were, “Don’t stop the show.”

Yevgeny Leonov (1926–1994)

Artistic Legacy

Leonov’s warmth and vulnerability made him the “everyman” of Soviet cinema. At the Moscow Theatre of Lenin’s Komsomol (LENT, Lenkom), he excelled in roles that balanced humour and pathos, such as in The Thunderstorm and The Inspector General. His filmography — from Gentlemen of Fortune (1971) to A Cruel Romance (1984) — showcased his ability to find humanity in even the most absurd situations.

Signature Roles

In Gentlemen of Fortune, his dual role as the gentle kindergarten teacher and the criminal “Docent” revealed his comedic range. As Kharitonov in A Cruel Romance, he brought tragic dignity to a man destroyed by class divides. His voice work — notably as Winnie‑the‑Pooh in the Soviet animated series — became a cultural touchstone.

Personal Anecdote

Leonov was famously modest. Once, when fans stopped him on the street to praise Gentlemen of Fortune, he replied, “That’s not me — that’s the character. I’m just Yevgeny, your neighbour.” He also loved gardening; colleagues said his dressing room was always filled with potted plants he tended between takes.

Mikhail Ulyanov (1927–2007)

Artistic Legacy

Ulyanov was a titan of the Vakhtangov Theatre, where his commanding presence and moral gravitas defined generations of Russian theatre. His stage roles — Richard III, Napoleon, and the Prophet in The Prophet — combined raw power with intellectual rigour. In film, he embodied authority and conflict, from the revolutionary chairman in Chairman (1965) to the tormented officer in Battleship Potemkin (1950).

Signature Roles

As Chairman Lukashin in Chairman, he portrayed a peasant leader torn between idealism and pragmatism, a role that earned him a Lenin Prize. His Napoleon in War and Peace (1967) was hailed for its psychological complexity. Later, as artistic director of the Vakhtangov, he championed new playwrights while preserving classical traditions.

Personal Anecdote

Ulyanov was known for his work ethic: he once rehearsed a 10‑minute monologue for 70 hours straight. Off‑stage, he was a devoted family man; his wife, actress Alla Kareva, said, “He carried the weight of the world on stage, but at home, he was our rock.” He also wrote essays on acting, arguing that “truth on stage begins with honesty in life.”

Lyubov Orlova (1902–1975)

Artistic Legacy

Orlova was the glittering face of Soviet cinema’s Golden Age, blending Hollywood glamour with socialist realism. At Moscow’s Music Hall and the Moscow Academic Theatre, she dazzled in musicals and comedies, while her film roles in Volga‑Volga (1938) and Circus (1936) made her Stalin’s favourite actress. Her performances combined athleticism, vocal prowess, and an almost surreal charm.

Signature Roles

In Circus, her portrayal of Marion Dixon — a performer fleeing racism in the West — became a symbol of Soviet progressivism. Volga‑Volga showcased her triple threat: singing, dancing, and comic timing. Her partnership with director Grigori Aleksandrov (her husband) produced seven films, each celebrating labour, love, and collective joy.

Personal Anecdote

Orlova’s discipline was legendary: she trained as a pianist at the Moscow Conservatory and maintained a rigorous exercise regimen into her 60s. Colleagues recalled how she would rehearse dance numbers until her muscles ached, insisting, “If it’s not perfect, it’s not worth doing.” Despite her glamorous on‑screen image, she lived modestly, donating much of her earnings to war orphans after WWII. Her husband, director Grigori Aleksandrov, once said, “Lyubov’s beauty was real — not just on film, but in her soul.”

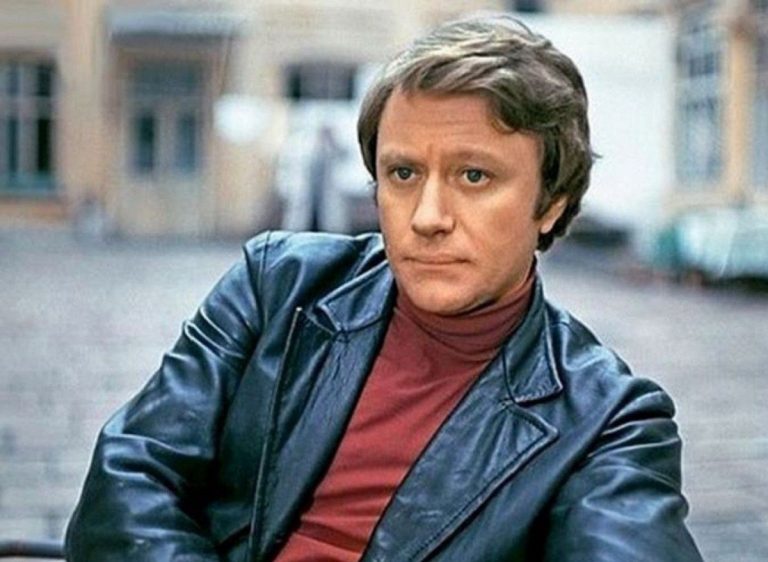

Alexander Abdulov (1953–2008)

Artistic Legacy

Abdulov was the charismatic heart of the Lenkom Theatre for decades, known for his athleticism, vocal range, and ability to blend romance with tragedy. His stage triumphs included the title role in The Wizard of Oz and the passionate Reznikov in Juno and Avos, a rock opera that became a cultural phenomenon. On screen, he excelled in both comedies (Formula of Love, 1984) and dramas (Gadfly, 1980), earning a reputation as a “people’s actor” beloved for his accessibility and warmth.

Signature Roles

In Formula of Love, his portrayal of the charming swindler Count Kalugin showcased his comedic timing and musical talent. As Arthur Burton in Gadfly, he brought a brooding intensity to the revolutionary hero. His role in Chance (1984) — a surreal comedy about identity — revealed his penchant for experimental storytelling. Critics praised his ability to make even flawed characters sympathetic through sheer presence.

Personal Anecdote

Abdulov was notorious for his pranks: he once convinced a fellow actor that a prop sword was cursed, sending the cast into hysterics. Off‑stage, he was a devoted father and philanthropist, organising charity performances for children’s hospitals. In his final years, despite battling illness, he continued performing, saying, “Theatre is my oxygen — I can’t stop breathing it.”

Oleg Menshikov (b. 1960)

Artistic Legacy

Menshikov emerged as a symbol of post‑Soviet theatre, blending classical training with avant‑garde daring. His breakout role in the TV film Pokrovskie Vorota (1982) made him an icon of Moscow’s intellectual youth, while his stage work at the Moscow Art Theatre (MKhAT) — including The Seagull and Three Sisters — demonstrated his mastery of Chekhovian ambiguity. As artistic director of the Yermolova Theatre since 2012, he has championed new playwrights while reviving classics with contemporary relevance.

Signature Roles

In Pokrovskie Vorota, his depiction of the witty, idealistic Konstantin Rukavishnikov captured the spirit of 1950s Moscow. In The Barber of Siberia (1998), he balanced romantic ardour with political intrigue. His portrayal of Hamlet (2005) at the Yermolova Theatre was hailed for its psychological depth, merging Shakespearean tragedy with Russian existentialism.

Personal Anecdote

Menshikov is known for his meticulous preparation: for The Barber of Siberia, he learned to play the violin and studied 19th‑century military protocols. Colleagues say he often arrives at rehearsals with annotated scripts, marking every pause and inflection. Off‑stage, he is a private figure, once remarking, “Acting is my public life; my real life is for those closest to me.”

Chulpan Khamatova (b. 1975)

Artistic Legacy

Khamatova is one of Russia’s most respected contemporary actresses, known for her emotional rawness and social engagement. At the Sovremennik Theatre and MKhAT, she has tackled roles ranging from Chekhov’s Nina Zarechnaya (The Seagull) to modern anti‑heroines. Her film work — particularly in Country of the Deaf (1998) and Children of the Arbat (2004) — explores trauma, resilience, and moral complexity. Beyond acting, she co‑founded the charity Podari Zhizn (“Give Life”), supporting children with cancer.

Signature Roles

In Country of the Deaf, her portrayal of Rita — a dancer navigating a world of violence and silence — earned critical acclaim for its physical and emotional intensity. In Children of the Arbat, her depiction of Varya Ivanova revealed the human cost of Stalinist purges. Theatre audiences praise her versatility: she can shift from the fragile Ophelia to the defiant Nora in A Doll’s House with equal conviction.

Personal Anecdote

Khamatova once revealed that she prepares for roles by immersing herself in the character’s world: for Country of the Deaf, she spent months learning sign language and observing deaf communities. She also juggled acting with charity work, often rehearsing late into the night before visiting hospitals. “Art and compassion are not separate,” she says. “They feed each other.”

Konstantin Khabensky (b. 1972)

Artistic Legacy

Khabensky has become a defining face of 21st‑century Russian cinema, known for his intellectual depth and moral integrity. After training at the Moscow Art Theatre School, he rose to fame in Night Watch (2004), a fantasy blockbuster that redefined Russian genre film. His stage work — including Three Sisters and The Seagull — showcases his classical roots, while his directorial debut, Sobibor (2018), demonstrated his commitment to historical storytelling. He also runs a charity foundation supporting children with brain tumours.

Signature Roles

In Night Watch, his portrayal of Anton Gorodetsky — a reluctant supernatural warrior — combined brooding introspection with action‑hero charisma. In Admiral (2008), he embodied the tragic figure of Admiral Kolchak, balancing romance and political tragedy. On stage, his Hamlet (2010) was praised for its modern relevance, exploring existential doubt in a chaotic world.

Personal Anecdote

Khabensky is renowned for his humility: he often declines interviews, preferring to let his work speak. For Sobibor, he spent two years researching the WWII death camp uprising, insisting on filming in Lithuania to honour the victims. Colleagues note his quiet determination: “He doesn’t seek fame,” one said. “He seeks truth — whether on stage, screen, or in life.”

Why Moscow?

These actors illustrate how Moscow’s theatres — from the Vakhtangov and Lenkom to MKhAT and Sovremennik — serve as incubators for talent. The city’s blend of imperial history, Soviet‑era institutions, and modern experimentation creates a unique ecosystem where actors refine their craft across stage, screen, and voice. Their collective legacy continues to inspire new generations, proving that Moscow remains Russia’s unrivalled stage.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.